The Current View

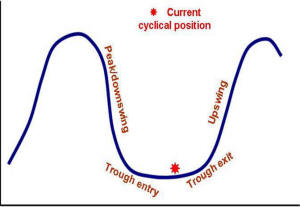

Growth in demand for raw materials peaked in late 2010. Since then, supply growth has generally outstripped demand leading to inventory rebuilding or spare production capacity. With the risk of shortages greatly reduced, prices lost their risk premia and have been tending toward marginal production costs to rebalance markets.

The missing ingredient for a move to the next phase of the cycle is an acceleration in global output growth which boosts raw material demand by enough to stabilise metal inventories or utilise excess capacity.

The PortfolioDirect cyclical

guideposts suggest that the best possible macroeconomic circumstances for

the resources sector will involve a sequence of upward revisions to

global growth forecasts, the term structure of metal prices once again

reflecting rising near term shortages, a weakening US dollar, strong money

supply growth rates and positive Chinese growth momentum. None of the five guideposts is "set to green"

(after the most recent adjustments in December 2016) suggesting the sector remains confined

to near the bottom of the cycle.

Has Anything Changed? - Updated View

From mid 2014, the metal market cyclical position was characterised as ‘Trough Entry’ with all but one of the PortfolioDirect cyclical guideposts - the international policy stance - flashing ‘red’ to indicate the absence of support.

Through February 2016, the first signs of cyclical improvement in nearly two years started to emerge. The metal price term structure reflected some moderate tightening in market conditions and the guidepost indicator was upgraded to ‘amber’ pending confirmation of further movement in this direction.

As of early December 2016, the Chinese growth momentum indicator was also upgraded to amber reflecting some slight improvement in the reading from the manufacturing sector purchasing managers index. Offsetting this benefit, to some extent, the policy stance indicator has been downgraded from green to amber. While monetary conditions remain broadly supportive, the momentum of growth in money supply is slackening while further constraints on fiscal, regulatory and trade regimes become evident.

US Wages Explain Slow Growth Scenario

U.S. labour market conditions are an important indicator of the world's

growth prospects.

U.S. employment income actually exceeds the value of US GDP by 1.7 trillion dollars a year and, as a result, is a critical determinant of the personal consumption spending which makes up two thirds of US GDP which contributes 16% to world output.

Higher U.S. wages are a double-edged sword. Stronger wages growth implies stronger growth in consumption spending and cyclically stronger economic conditions.

On the flip side, higher wages create fresh anxieties about inflation and add to the risks of higher interest rates than currently anticipated.

Data released in the past week have pointed to still

moderate growth in wages. Hourly wages of private sector production

workers increased by just 2.4% over the 12 months ended January 2017.

The recent trend in wages growth has been a clear step down from the 4% top of the cycle pace of growth which had prevailed prior to 2008.

The moderation in wages growth acts against expectations of a resurgence in U.S. GDP growth and, as a consequence, a cyclically stronger global economy.

Employment - the other element in the total national wages bill - tends to rise most strongly when wages growth is relatively weak. As wages growth has accelerated through the U.S. economic cycle - even if only very moderately - employment growth has stabilised.

The current 2% rate of employment growth is consistent with historical growth outcomes.

Whereas persistence of such growth in the numbers of employees has typically resulted in strengthening wages growth, the historic relationship has not been so evident recently.

As with so much in economics, wages, employment and interest rates are interconnected.

Slow growth in wages is a sign of subdued inflation

pressures and validation of historically low bond yields.

Higher output growth has usually been thought of as incompatible with rising inflation due to the negative impact of tightening monetary policy in response on activity. In reality, a surge in inflation expectations may be what is needed to break the links holding back stronger output growth.

Higher inflation expectations would add upward pressure to wage demands. Initially, higher wages would add to consumption spending and domestic output. Rising corporate incomes would loosen some of the constraints on wages growth to create a benign chain of outcomes favouring growth.

Most likely, these events would quickly result in higher market interest rates and more aggressive policy settings to curtail a blow-out in prices and, at some point, the growth outlook would again be under pressure but the current shackles will have been broken.

The route to stronger growth does not occur without some break in current economic relationships.

Central banks in Europe, Japan and the USA have been failing in their attempts to rekindle inflation pressures. They have shown how little control they can exert over inflation outcomes.

The theory of a close connection between money supply and the prices of goods and services has been disproved - although a connection between money supply and asset prices has been the demonstrated repeatedly.

These conditions could persist indefinitely in which case one of the underpinnings for a genuine cyclical recovery in commodity prices will have been compromised.