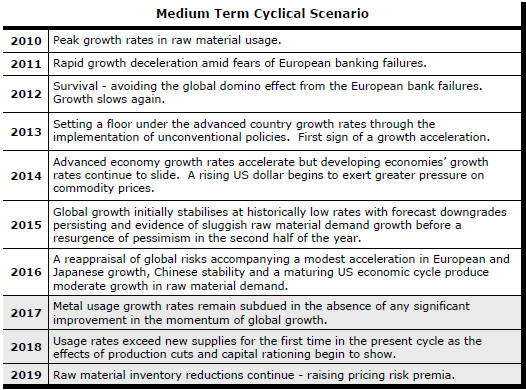

The Current View

Growth in demand for raw materials peaked in late 2010. Since then, supply growth has generally outstripped demand leading to inventory rebuilding or spare production capacity. With the risk of shortages greatly reduced, prices lost their risk premia and have been tending toward marginal production costs to rebalance markets.

The missing ingredient for a move to the next phase of the cycle is an acceleration in global output growth which boosts raw material demand by enough to stabilise metal inventories or utilise excess capacity.

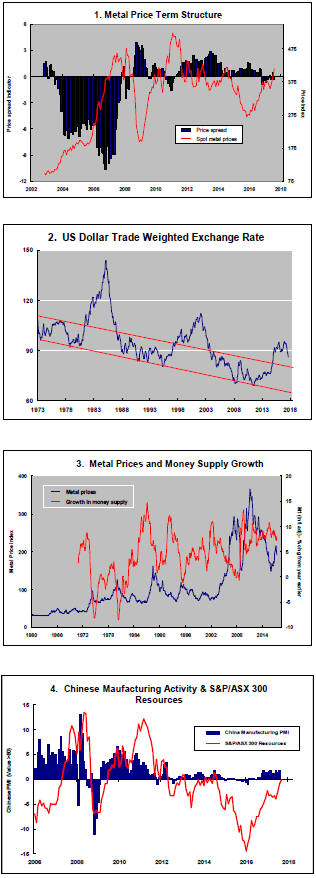

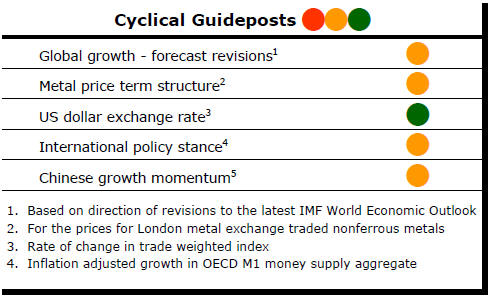

The PortfolioDirect cyclical

guideposts suggest that the best possible macroeconomic circumstances for

the resources sector will involve a sequence of upward revisions to

global growth forecasts, the term structure of metal prices once again

reflecting rising near term shortages, a weakening US dollar, strong money

supply growth rates and positive Chinese growth momentum. Only one of the five guideposts is "set to green"

(after the most recent adjustments in July 2017) suggesting the sector remains confined

to near the bottom of the cycle.

Has Anything Changed? - Updated View

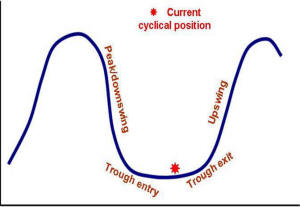

From mid 2014, the metal market cyclical position was characterised as ‘Trough Entry’ with all but one of the PortfolioDirect cyclical guideposts - the international policy stance - flashing ‘red’ to indicate the absence of support.

Through February 2016, the first signs of cyclical improvement in nearly two years started to emerge. The metal price term structure reflected some moderate tightening in market conditions and the guidepost indicator was upgraded to ‘amber’ pending confirmation of further movement in this direction.

As of early December 2016, the Chinese growth momentum indicator was also upgraded to amber reflecting some slight improvement in the reading from the manufacturing sector purchasing managers index. Offsetting this benefit, to some extent, the policy stance indicator was been downgraded from green to amber.

The most recent change in cyclical guidepost positioning has been at the end of July 2017 when the exchange rate guidepost was upgraded to green.

(The following article was first published in Mining Journal on 6 July 2017)

Model Mining Code too Hard

Cutting across

cyclical conditions is a global campaign to regulate how the benefits of

mining are shared between companies and other stakeholders with an interest

in project development outcomes.

A universally adopted model mining code sounds preferable to capriciously applied or ill-defined rules but the choice is more nuanced and less straightforward.

Mining codes serve two principal purposes. They must offer investors confidence about the security of their capital. At the same time, they must accommodate the expectations of all stakeholders about the distribution of benefits from mineral developments.

More often than not, the two purposes are compatible. Tensions arise when expectations differ and parties are unprepared to compromise.

The mining industry is not alone in challenging policymakers to resolve competing social and economic interests. Central banks trying to juggle full employment and low inflation mandates are an example at the macro level.

Drug pricing, internet access, media ownership rules, gambling licences, bank regulation, motor vehicle manufacturing and, recently, the impact of ride sharing businesses on licensed cabs are a few other instances where governments must arbitrate a sometimes uneasy compromise between providers of capital and other stakeholders.

Liberal democracies prefer to resolve such tensions through day to day political processes and periodic elections, leaving open the possibility that previously agreed arrangements may change.

Even in the best governed jurisdictions, governments will retain some discretion to respond to unanticipated innovation or unforeseen macro events.

A comprehensive mining industry code cannot be separated entirely from policies about trade, capital movement and migration over which governments are reluctant to cede control or take guidance from others.

In any event, mining may only tangentially impact more deep-seated national problems.

On 28 June 2017, the National Resource and Governance Institute (NRGI) released what it described as the most comprehensive cross-country study of extractives governance in “the only international index dedicated to resource governance”.

The NRGI tried to bolster the moral standing of its efforts by claiming that the trillions of dollars produced by the resources industry “contrast cruelly with the poverty of many countries where resources are found”.

The predicament of millions of people in Libya, Afghanistan, Iraq, Venezuela, Yemen and South Sudan – not the worst rated of the 81 countries covered by the index - needs addressing but surely the contribution of a mining code to the solution is easily exaggerated.

The research body described Eritrea as having the worst resource governance among the countries surveyed. In contrast to this widely held view of Eritrean governance shortcomings, the chief executive of ASX miner Danakali has been consistently adamant that no such problem exists, drawing on his experience developing a huge potash find in the country.

Danakali is effectively saying that surveys of country risks, based on the opinions of researchers and academics, are too general to be worthwhile or fail to give those with direct operating experience sufficient weight. They overstate the need for stronger mining code models.

The Fraser Institute annual survey of mining companies reviews Eritrea far more favourably.

In any case, an investor needs to look ahead. Danakali contends that Eritrean mining industry governance structures will experience a seamless transition after President Isaias Afwerki, who has not permitted an election since taking power in 1993, relinquishes office.

However adept the next generation of Eritrean leaders are at fashioning governance structures, the market value of Danakali could easily decline 20-40% upon the president’s demise and amid the ensuing uncertainty about what comes next. The text of a mining code will matter little.

The NRGI itself points out, too, that “more progress is taking place in the adoption of rules than in their actual practice”.

A country’s mining code is just one element in a complex mix of corporate, legal, political, social and macro-cyclical issues even in the most sophisticated jurisdictions.

Citic Pacific, operator of the multi billion dollar Sino iron ore project in Western Australia, is in the midst of a bitter dispute with the Clive Palmer controlled Mineralogy over royalties.

Faced with big losses, the Chinese company would dearly love to extricate itself from any payment obligations. Palmer is a notoriously obstreperous business partner. Both signed a contract under which Palmer was to receive payments based on future values of the then prevailing benchmark iron ore price.

Citic is claiming in the Western Australian supreme court that abandonment of benchmark pricing means Mineralogy should get no payment. Citic is instead offering an equity stake in the loss making project. Palmer, meanwhile, is threatening to bring the project to its knees if he does not receive a sufficiently generous stream of cash. Citic is threatening mutually assured destruction if it is forced to comply.

An atrociously drafted contract between the two parties has jeopardised the anticipated community benefits of the project. Many governments would be sorely tempted to impose a solution even at the risk of abandoning their mining codes and both companies losing their capital. Few might complain.

In New South Wales, the mining code has been effectively rewritten by the courts and anti-corruption prosecutors.

Last month, the state’s supreme court sentenced a former mines minister to jail for 7-10 years for the way in which he had granted a coal exploration licence to a business group which included a former union powerbroker known to the minister.

According to the evidence, the minister did not receive any benefit himself. Legislation allowed the minister a discretion but the court found that he should have done more to get a better deal for the state and should be punished for not doing so.

In a stronger market with competition for tenements, this newly imposed obligation to maximise state benefits could only mean less tenement security for explorers.

A model covering all these eventualities seems an implausibly unrealistic goal. Reliance on market incentives may be the best way forward.

Enforced uniformity ensures everyone is wrong at the same time and countries lose the benefits from regulatory competition across jurisdictions.

Policy progress is often driven by lessons learned elsewhere. Countries or provinces trying out different governance approaches can help spur improvement.

The best model may be no model at all.