The Current View

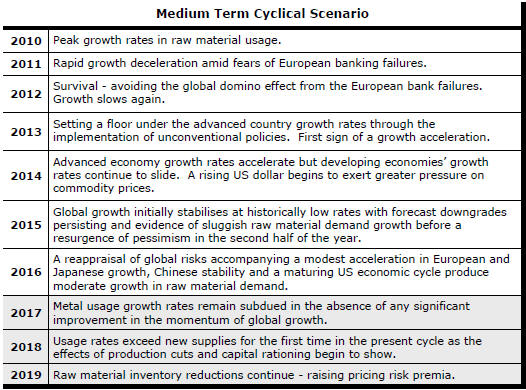

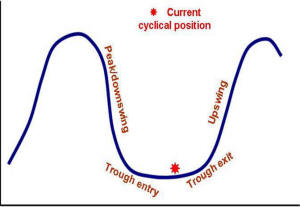

Growth in demand for raw materials peaked in late 2010. Since then, supply growth has generally outstripped demand leading to inventory rebuilding or spare production capacity. With the risk of shortages greatly reduced, prices lost their risk premia and have been tending toward marginal production costs to rebalance markets.

The missing ingredient for a move to the next phase of the cycle is an acceleration in global output growth which boosts raw material demand by enough to stabilise metal inventories or utilise excess capacity.

The PortfolioDirect cyclical

guideposts suggest that the best possible macroeconomic circumstances for

the resources sector will involve a sequence of upward revisions to

global growth forecasts, the term structure of metal prices once again

reflecting rising near term shortages, a weakening US dollar, strong money

supply growth rates and positive Chinese growth momentum. None of the five guideposts is "set to green"

(after the most recent adjustments in December 2016) suggesting the sector remains confined

to near the bottom of the cycle.

Has Anything Changed? - Updated View

From mid 2014, the metal market cyclical position was characterised as ‘Trough Entry’ with all but one of the PortfolioDirect cyclical guideposts - the international policy stance - flashing ‘red’ to indicate the absence of support.

Through February 2016, the first signs of cyclical improvement in nearly two years started to emerge. The metal price term structure reflected some moderate tightening in market conditions and the guidepost indicator was upgraded to ‘amber’ pending confirmation of further movement in this direction.

As of early December 2016, the Chinese growth momentum indicator was also upgraded to amber reflecting some slight improvement in the reading from the manufacturing sector purchasing managers index. Offsetting this benefit, to some extent, the policy stance indicator has been downgraded from green to amber. While monetary conditions remain broadly supportive, the momentum of growth in money supply is slackening while further constraints on fiscal, regulatory and trade regimes become evident.

Poor Governance? Blame the Cycle

Adherence to strong governance practices among junior mining companies,

always short of perfect, has been further eroded by prolonged cyclical

weakness and a reticence to invest by traditional supporters of the sector.

Terramin Australia directors recently suffered embarrassing defeats over remuneration practices at the hands of shareholders.

Two-thirds of those voting at the annual meeting in May rejected the company’s remuneration report. The board was also forced to withdraw resolutions relating to fees for directors.

The Algerian zinc mine developer has not explained why a large chunk of its shareholder base was so displeased but no one should have been surprised.

The withdrawn resolutions had allowed directors to claw back board fees foregone during 2016 via an issue of shares in lieu of cash payments.

Since the Terramin share price has risen by as much as 120% over the past year, the retrospective grant of shares at historical prices would have created an immediate windfall for the beneficiaries. They would have received a far greater benefit than if cash payments had been made when they were due.

Boards are prone to such stumbles without appropriately diverse membership and effective independent voices. These tendencies have been heightened by cyclical pressures to conserve cash.

Cutting back on board numbers has put governance standards at risk by encouraging concentrations of power among directors tied to management or investors supplying critically important funds.

Expected governance standards are well defined. ASX requires listed companies to say why they have departed from its published principles.

In practice, it is easy enough for companies to skirt governance guidelines by simply asserting that they are too small to comply.

Unfortunately, among small miners, the distinction between management and board is an especially vulnerable principle.

The blurred and sometimes erased boundary between executives and directors is often the source of angst among investors about remuneration practices.

ASX governance principles highlight the role remuneration plays in the oversight function within a publicly listed company. The principles state that companies “need to ensure that the incentives for non-executive directors do not conflict with their obligation to bring an independent judgement to matters before the board”.

Adherence to the ASX principles also requires that “no individual director or senior executive should be involved in deciding his or her own remuneration”.

The principles go on to say that the company’s policies and practices “should appropriately reflect the different roles and responsibilities of non-executive directors compared with executive directors and other senior executives”.

The ASX guidelines advise that “non-executive directors should not receive performance-based remuneration”.

Northern Minerals has asked its shareholders to approve remuneration arrangements for a new director at a meeting on 27 June.

The Western Australian dysprosium mine developer immodestly described its remuneration principles as being “in accordance with best practice corporate governance” in its annual report for the year ended June 2016.

Feigning consistency with the ASX principles, Northern Minerals characterised the structure of its own non-executive director and executive remuneration in its latest remuneration report as being “separate and distinct”.

The company stated unambiguously that “there is no direct link between remuneration paid to any of the directors and corporate performance such as bonus payments for achievement of certain key performance indicators”.

Notwithstanding such worthy sentiments and the pretence of compliance with the ASX principles, all Northern Minerals directors, executive and non-executive alike, have received share based benefits tagged to performance indicators.

Shareholders are now being asked to approve a grant of equity-based performance rights to Mr Nan Yang “in line with Performance Rights approved for the other Directors”.

Mr Nan Yang is a nominee of Huatai Mining which is now the largest ongoing funder of Northern Minerals with a commitment to provide $30 million.

A section of the explanatory memorandum accompanying the notice of meeting is promisingly headed “Reasons for the specific number of the Proposed Performance Rights”. Someone must have thought shareholders deserved an explanation but why 2.5 million shares were up for grabs and not 250,000 or 25 million is left undocumented.

Why a shareholder nominee, reporting to an outside entity, should be given any incentives is also left unsaid. The existing directors, who have either proposed or confirmed performance rights for each other, simply reasserted the desirability of such a reward mechanism for the newcomer.

Performance rights have also been granted to three executives of the Conglin group, another large Northern Minerals shareholder. One current director of the company, her alternate and the Conglin group’s chief executive, their boss and executive chairman of Northern Minerals until March 2017, are beneficiaries.

The erosion of governance oversight goes further in this case. The current Northern Minerals managing director is also chairman of Lithium Australia and de facto head of its remuneration committee. The managing director of Lithium Australia, meanwhile, is one of only two members of the Northern Minerals remuneration committee.

Many, if not most, of these governance compromises arise from the cyclical pressures on industry funding. Companies forced to juggle cash conservation and unsympathetic capital markets with governance priorities leave investors with an awkward choice.

On paper, at least, none of Mr Nan Yang or his fellow directors can independently exercise unconflicted judgements about the progress of the company, its social responsibilities, its obligations to minority shareholders or the activities of management and their payments.

The vast bulk of Northern Minerals investors are being asked to take a chance that abandoning generally agreed governance principles is for the greater good. Against convention wisdom, they are being asked to accept that remuneration packages structured to ensure a commonality of interests do not neuter independent thought.

In reality, no one looking in from outside knows exactly how members of the board interact with one another, how their motivations may differ and the extent to which mutually reinforcing performance rights contribute positively to corporate outcomes.

Presumably, directors will say the board is functioning well for the benefit of all shareholders.

True or not, Northern Minerals directors find themselves embracing the façade of sound governance practices as they do something completely different. That alone is a problem.