The Current View

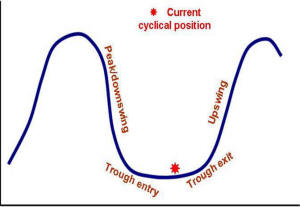

Growth in demand for raw materials peaked in late 2010. Since then, supply growth has generally outstripped demand leading to inventory rebuilding or spare production capacity. With the risk of shortages greatly reduced, prices lost their risk premia and have been tending toward marginal production costs to rebalance markets.

The missing ingredient for a move to the next phase of the cycle is an acceleration in global output growth which boosts raw material demand by enough to stabilise metal inventories or utilise excess capacity.

The PortfolioDirect cyclical

guideposts suggest that the best possible macroeconomic circumstances for

the resources sector will involve a sequence of upward revisions to

global growth forecasts, the term structure of metal prices once again

reflecting rising near term shortages, a weakening US dollar, strong money

supply growth rates and positive Chinese growth momentum. None of the five guideposts is "set to green"

(after the most recent adjustments in December 2016) suggesting the sector remains confined

to near the bottom of the cycle.

Has Anything Changed? - Updated View

From mid 2014, the metal market cyclical position was characterised as ‘Trough Entry’ with all but one of the PortfolioDirect cyclical guideposts - the international policy stance - flashing ‘red’ to indicate the absence of support.

Through February 2016, the first signs of cyclical improvement in nearly two years started to emerge. The metal price term structure reflected some moderate tightening in market conditions and the guidepost indicator was upgraded to ‘amber’ pending confirmation of further movement in this direction.

As of early December 2016, the Chinese growth momentum indicator was also upgraded to amber reflecting some slight improvement in the reading from the manufacturing sector purchasing managers index. Offsetting this benefit, to some extent, the policy stance indicator has been downgraded from green to amber. While monetary conditions remain broadly supportive, the momentum of growth in money supply is slackening while further constraints on fiscal, regulatory and trade regimes become evident.

Industry Profits Surprise Government

A $30 billion profit surge from an enlarged Australian resources industry

was a recent godsend for government budgeting but an ominous sign of future

policymaking challenges.

March quarter data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), published at the beginning of June, show the changing nature of the ties between the Australian economy and commodity markets.

The ABS reported that resource sector quarterly profits before tax, including those from oil and gas, rose 311% to an annual rate of $71 billion between the end of September 2016 and the end of March 2017. They accounted for 30% of total Australian corporate profits.

Prior to this recent rise, all the post-2004 industry

profit gains which had accompanied the so-called supercycle had

disappeared. A $506 billion capital spending spree had failed to produce a

positive financial return.

Lost profitability aside, important macro benefits came with the industry’s 10 year investment binge which accounted for 24% of total private business spending.

Every dollar spent on new equipment or structures came with more jobs, higher wages and stronger demand nationwide for goods and services. No part of the Australian economy would have been untouched.

Helped by its exposure to the minerals industry, the Australian economy rode out a succession of macro threats without recession for over two decades.

The ABS data for the March quarter showed a declining but still elevated capital spend by the industry in Australia.

Including exploration, industry spending fell to $40.3 billion over the 12 months to March 2017 from a peak rate of $94.2 billion in 2012. Despite the fall, capital expenditure remained more than four times higher than the $9.7 billion in 2002 before the cyclical expansion of the industry got underway.

The spending surge has brought big capacity increases. Black coal output rose from an average 361 million tonnes in 2002-04 to 566 million tonnes in 2016. Iron ore output rose by 647 million tonnes. Gas production has risen from 37.2 to 97.3 million cubic feet with a further 40% increase expected.

Higher production rates now put Australia firmly into the second phase of its resources cycle.

Investment spending might remain well below the frenzied heights of 2012-2014 for decades to come but the country’s profit potential has risen dramatically.

The increase in profits during the most recent December-March quarters brought the industry to within just 15% of top-of-the-cycle profits in 2011.

The improvement came overwhelmingly from higher coal and iron ore prices.

According to data released by the Australian government’s Department of Industry, black coal production was little changed over the year to March 2017 but average metallurgical coal prices more than doubled and lower valued thermal coal prices increased 40%.

The upshot of the coal price movements was a $6.3 billion surge in quarterly export income nearly all of which, in the short term, would have fallen to the bottom lines of the exporting companies.

Similarly, a 45% price rise resulted in a $6.8 billion surge in quarterly iron ore income.

The improved industry profitability, if sustained, would be equivalent to an extra $55 billion a year.

Unfortunately, the macro impacts of investment spending far outweigh the consequences of an equivalent dollar value of profits.

The most immediate benefit of higher profits is that governments can paper over some of their shortfalls in taxation receipts.

Beyond the fiscal effect, the impact is more thinly stretched. Some profits will be distributed to shareholders, most of who will reside outside Australia. The balance retained by companies will help sustain investment spending at a higher level than might otherwise be the case but a portion will be retained for a rainy day and contribute to debt reduction.

As well as the evident benefit for cash strapped governments, the rapid movement in industry profits contains a warning sign.

The resources industry is the most likely source of an exogenous income shock for the Australian economy. Whether Australian income growth is unexpectedly strong or surprisingly weak will depend heavily on global raw material markets.

With the value of the nation’s principal mineral commodity exports more than ever a product of short term macro influences, governments face larger swings in tax collections than they have been used to managing.

Australia increasingly faces conditions similar to those of large oil exporters forced to align their budgets to swings in oil prices.

The Australian government shows no special skill in understanding what drives the key markets on which it is relying for a large part of its revenue base.

A year ago, the government’s in-house agency specialising in forecasting commodity price swings had expected coal and iron ore export receipts in 2016/17 of $80.7 billion. Once commodity prices started to rise, it upped its forecast. By midway through the year, its forecast was $47 billion higher.

On 7 July 2017, the agency cut back estimated iron ore export earnings for the just completed financial year by 10% in reaction to the subsequent decline in prices.

At an official level, forecasts have usually been driven by extrapolating what has just happened rather than an understanding of future market conditions.

With the expanded size of the industry and prices increasingly sensitive to small market balance changes, government revenue projections appear more susceptible to error and uncertainty. Multi year budgeting and implementing debt reduction plans will become tougher.

Developing countries are constantly urged to manage their fiscal positions so as to avoid spending anticipated commodity market windfalls before they occur. Some have set up independently managed special funds to smooth the impact of commodity revenues.

The Australian government has no such programs in place and, for all practical purposes, had already spent the unexpectedly improved revenues that came its way in the past year. .