The Current View

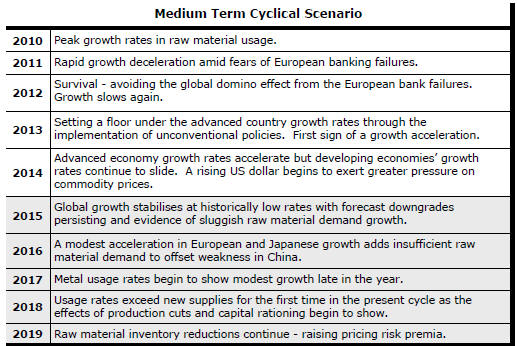

Growth in demand for raw materials peaked in late 2010. Since then, supply growth has continued to outstrip demand leading to inventory rebuilding or spare production capacity. With the risk of shortages greatly reduced, prices have lost their risk premia and are tending toward marginal production costs to rebalance markets.

To move to the next phase of the cycle, an acceleration in global output growth will be required to boost raw material demand by enough to stabilise metal inventories or utilise excess capacity.

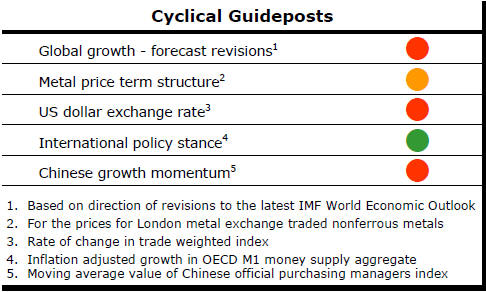

The PortfolioDirect cyclical

guideposts suggest that the best possible macroeconomic circumstances for

the resources sector will involve a sequence of upward revisions to

global growth forecasts, the term structure of metal prices once again

reflecting rising near term shortages, a weakening US dollar, strong money

supply growth rates and positive Chinese growth momentum. Only one of

the five guideposts is "set to green" suggesting the sector remains confined

to the bottom of the cycle .

Has Anything Changed? - Updated View

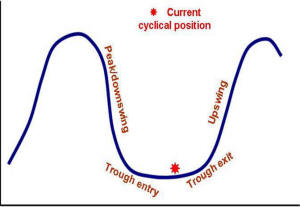

Since mid 2014, the metal market cyclical position has been characterised as ‘Trough Entry’ as prices have remained in downtrend with all but one of the PortfolioDirect cyclical guideposts - the international policy stance - flashing ‘red’ to indicate the absence of support.

The absence of a global growth acceleration, a stronger dollar and flagging Chinese growth momentum remain critical features of the current cyclical positioning.

Through February 2016, the first signs of cyclical improvement in nearly two years started to emerge. After 15 months of contango, the metal price term structure shifted to backwardation reflecting some moderate tightening in market conditions.

The metal price term structure is the most sensitive of the five cyclical guideposts to short term conditions and could, consequently, quickly reverse direction. Nonetheless, this is an improvement in market conditions and the guidepost indicator has been upgraded to ‘amber’ pending confirmation of further movement in this direction.

Brexit Vote Hits Miners’ Growth Outlook

Even before the Brexit vote, miners had reason to worry about the prospect

of a lengthening cyclical trough.

The decision of UK electors to quit the European Union signals the onset of a possibly intractable political crisis but not necessarily a financial crisis. For the mining industry, the added drag on global growth matters most.

The UK vote to leave Europe consolidated the impression that global growth will be insufficient to tilt market balances away from surpluses.

Much of the financial market nervousness so evident in the immediate aftermath of the UK referendum arises from the experiences of 2008. Then, disruptions to unforeseen and highly complex financial connections across countries, security types and institutions led to liquidity failures.

In contrast to 2008 and, before it, the Asian financial crisis in 1997 and the Long Term Credit Management failure precipitated by Russia’s 1998 debt default, market responses to the Brexit vote have been generally calm and orderly.

Unlike those earlier instances, central banks have not had to shore up financial institutions although they have felt compelled to reassure them of their readiness to act should circumstances change.

Fortunately and in contrast to other European countries, the UK has its own currency allowing prices to begin adjusting immediately. Despite some tendency to overshoot, a relatively sophisticated asset pricing regime will play an important role in recovery.

In the longer term, too, some in Europe may even come to thank the British for their bravery in quitting the union.

One of the drawbacks of European integration has been a resulting slowness to adapt to economic forces. The necessity to redesign the union, including the structure of its financial intermediation, in response to the UK departure will provide an opportunity to reform otherwise sclerotic institutions that have been failing the entire European membership.

Although severe, market reactions to the British referendum vote have shown some rationality.

Understandably, sterling dropped dramatically. Investment flows into the UK and within the economy are likely to stall, even to the extent of precipitating recession, until new political and economic rules are established and understood.

Re-crafted institutional arrangements will be needed. In particular, financial institutions with European trading headquarters in London will have to assess whether they will be more profitably located somewhere else. Unsurprisingly, banks have taken the brunt of the negative equity market reaction to the vote.

The Nikkei 225 immediately fell by over 9% but Japan faced a double whammy. The Brexit flight to safety forced up the yen which adversely affects the competitiveness and earnings of Japanese exporters and makes it harder for the government to reflate the economy.

In the USA, the share prices of companies with the largest exposures to the UK took the biggest hits. Some with a more domestic orientation actually gained ground despite the widespread market weakness.

These signs of prices doing their job suggest avoidance of a financial calamity.

But for Brexit, the primary purpose of this week’s ‘From the Capital’ column would have been to draw attention to recent comments by St Louis Federal Reserve Bank president James Bullard.

Bullard will not have been a well-known name within mining circles but his remarks on 17 June hold deep significance for the industry’s outlook.

The Federal Reserve, in common with many industry analysts, has been assuming a gradual return of financial asset prices to historical averages. Hence those on the FOMC, like Bullard, have for years been speaking about ‘normalisation’.

The triple forces of new regulations, large fiscal deficits and historically easy monetary conditions originating from 2008 have been disappointingly slow in reigniting global growth and creating the conditions which would facilitate a return to historically average monetary settings.

In addressing the media at the conclusion of the June FOMC meeting in Washington two days before Bullard spoke, Fed chair Janet Yellen seemed more hesitant than ever in her depiction of the economic outlook and likely future policy stance.

Yellen characterised the outlook as having changed only slightly. While true that the most recent forecast changes from the governors had only been slight and seemingly immaterial on their own, they have been the latest in a long sequence.

Viewed over a prolonged period, changes in interpretation have been dramatic. In particular, the connection between the onset of higher inflation and improved labour market conditions has been well beyond the bounds of what had once been expected.

Reflecting some frustration over this disparity between promise and outcome, Bullard is arguing for a break with the past. There was no point in bracing for a return to historically average prices, he said, without evidence of the conditions necessary for such a change. It would be better, on his reckoning, to assume a continuation of the existing economic regime until a change was evident.

Bullard opined that current policy settings were already optimal for the existing slow growth economic regime. Bullard’s “new characterization” meant one more interest rate rise in 2016 with no more being needed before the end of 2018.

This radical departure from the conventional wisdom is close to saying that normalisation is off the agenda for the foreseeable future despite having been the preoccupation of policymakers for several years.

If adopted, the Bullard model would leave policymakers little ammunition with which to counter a normal cyclical slowdown in growth over the next two years let alone anything approaching a financial crisis.

No upside and greater risk of downside is the growth outlook implied by Bullard’s evolving view of the world.

Even without Brexit dampening the outlook, a mining industry whose prospects rely overwhelmingly on resurgent growth would have had cause to ponder a bleaker future. .